Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

It’s time for women to reclaim the kitchen as an empowering place

Being in the kitchen comes with a lot of baggage for many women due to cooking and feminism's complicated history. But cooking can be empowering—here's why.

There’s a scene in the *ahem* Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Fifty Shades Freed where the protagonist, Ana, is cooking and her husband, Christian, makes some comment about how he likes to see her in the kitchen. “Barefoot and pregnant?” she jokes. (I’m sure there’s a different pop culture moment I could reference to open up this discussion, but none are as embarrassing as one that admits to the entire internet that I’ve read all three Fifty Shades novels.) I remember reading that part and thinking, LOL if any man ever said that to me, I would not be down. “I could get used to you in the kitchen.” Blah. Invoking my safe word.

My gut reaction to this scene is so strong because it immediately conjures images of the Mad Men era, during which time picture-perfect Betty Drapers, wearing waist-cinching aprons and pumps, were expected to make pot roasts and watch the kids while their husbands went off to work. Heck, even the Joan Holloways (women who had jobs) were forced to prepare the meals after spending all day at work. Because, for much of history, the kitchen has been considered “the woman’s domain.”

To understand why this is, we have to back up a couple hundred years. Prior to the 19th century, there wasn’t this split between domestic spaces and public spaces (often called spheres), says Catherine Allgor, president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, who’s also on the board of directors for the National Women’s History Museum. Most people were farmers, and “the home was the center of production,” Allgor says. “The men and the women were together in the enterprise of producing [their commodities] on the farm.”

But when a middle class began to emerge in the mid-1800s, more men began to work at jobs that required them to leave the house—for instance, at a bank—”and women were now relegated to homes that were no longer the center of production,” Allgor says. “There began to be this really strong prescriptive literature [in women’s magazines, books, and religious writings] about the role of the house” and a woman’s place within it.

“Woman was the hostage in the home…The attributes of True Womanhood, by which a woman judged herself and was judged by her husband, her neighbors, and her society could be divided into four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.” —Barbara Welters, “The Cult of True Womanhood” (1966)

In a landmark essay written by the historian Barbara Welter in 1966, she describes this new “cult of True Womanhood” thusly: “Woman…was the hostage in the home. In a society where values changed frequently, where fortunes rose and fell with frightening rapidity, where social and economic mobility provided instability as well as hope, one thing at least remained the same—a true woman was a true woman, wherever she was found…The attributes of True Womanhood, by which a woman judged herself and was judged by her husband, her neighbors, and her society could be divided into four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. Without them, all was ashes. With them, she was promised happiness and power.”

This link between a woman’s character and her ability to take care of the home really stuck. “These roles were gendered for so long that men didn’t want to [take part in domestic duties] because it was ‘women’s work,'” says Allgor. And because women were seen as lesser than men, their work was seen as less important.

Parity in domestic duties is very much still a work in progress—today, women comprise 47 percent of U.S. workers, but they still shoulder most of the load when it comes to household upkeep; a 2015 survey from the U.S. Department of Labor found that “on an average day, women spent more than twice as much time preparing food and drink and doing interior cleaning.” But we don’t need to wait for a 50/50 split before women can begin to reclaim their agency in the kitchen. Women don’t need to be “hostages” in this space, and cooking doesn’t need to be seen as a service provided to others.

Women don’t need to be “hostages” in this space, and cooking doesn’t need to be seen as a service provided to others.

“I think that knowing what you put into your body is really empowering,” says Nicole Rice, co-founder and president of Countertop Foods. “Knowing that you can cook something really delicious—and healthier than your favorite restaurant—is really amazing.” Furthermore, the act of cooking can even be meditative, and a form of self-care. “The process of following a recipe, measuring ingredients, paying attention to textures and smells, and even setting the table fall into the category of ‘executive function’ skills,” Ruschelle Khanna, LCSW, previously told Well+Good. “When we have strong executive function skills we also tend to manage anger and regulate emotions more effectively.”

Far from the isolating practice it once was, cooking itself has also become more of a social act. “Dinner parties are coming back in style,” Rice says. The traditional idea of the dinner party has the woman stuck in the kitchen by herself, cooking and catering to everyone else’s needs. Now, dinner parties include cooking as part of the main event. I’ve noticed this as well—when I visit friends’ homes, often the cooking duties are spread out among the guests. And as Khanna says, “Sharing meals promotes community. Community prevents isolation, which leads to a number of chronic health conditions.”

Allgor leaves me with the reminder, however, that even as we shift our perspective on cooking, it’s important to continue the work of shifting the burden of household duties. Closing the gender gap will help to further break down the idea that a woman’s worth is directly proportional to her domestic skills. Then, finding “happiness and power” through her cooking will be her choice, not her fate.

This week on Well+Good, we’re launching Cook With Us, a new program designed to help you do just that. We believe that cooking is an important piece of the wellness puzzle and that everyone can make magic (or at least some avo toast) happen in the kitchen. Sometimes, you just need someone to show you where to start, and maybe a few others cheering you on. It doesn’t need to be complicated, or every day—like most things in the wellness world, a little goes a long way.

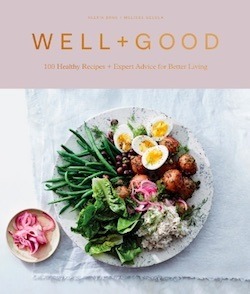

Make a promise to start cooking tonight (maybe snag a copy of our cookbook) and meet us in the kitchen.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.