Are big tech’s digital well-being initiatives actually helping people unplug?

Apple, Google, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube have introduced features and apps to limit screen time, but it's hard to say if they're actually working.

Around 9 a.m. every Sunday, my iPhone buzzes, and I instantly start feeling a little queasy. Without even looking, I know what the notification is: a detailed record of all the time I’ve spent scrolling, tapping, and swiping for the past seven days. And I know I’m going to be mildly horrified by what I see.

Last week, for instance, I learned that I picked up my phone an average of 46 times per day, adding up to a daily screen-gazing average of four hours and 14 minutes. Most of that time—almost two hours per day—I was on Instagram and Facebook, and I spent an hour texting, and an hour on email. I also lost two full hours of the week to falling down Google rabbit holes (like to conduct very important research into what all the Family Matters cast members are up to). I’d like to say that this is out of the ordinary for me, but I’ve calculated that it’s actually a 20 percent improvement from when my iPhone first started cluing me in to my digital habits.

When I get these alerts each week—part of Apple’s Screen Time initiative, which launched last September—I feel guilty and a little embarrassed, kind of like when I look at my latest bank statement and realize I spent $100 on iced coffees last month. Sure, a few minutes of scrolling through my feeds here and there seems harmless in the moment. But it all adds up to a lot of time that I could have spent doing more fulfilling things. In those four hours and 14 minutes per day, I could have started writing a novel. I could have gone on a long hike or gone out for an even longer lunch with friends—all the things I often tell myself I don’t have time to do. Yet, instead, I spend those precious hours spacily scrolling through photos of my childhood acquaintances’ kids and taking a quiz to find out what kind of dog I most resemble. (A golden retriever, in case you were wondering.)

Not that it’s all bad. I get a lot of professional inspiration from Instagram, and I love that Facebook, iChat, and email allow me to stay connected to (or, stalk) friends and family in other parts of the world. But most of the time, I’m not using technology in a mindful way. Maggie Stanphill, director of user experience on Digital Wellbeing at Google, an initiative the company launched last year, says that I’m not alone in feeling this way. “The research [Google has done] found that many people have a bit of a love-hate relationship with their phones,” she says. “While most people really enjoy the access to information and resources that tech provides, there are also many who feel stress and frustration from their inability to easily disconnect from using their phones.”

The big tech companies are listening. Within the past year or so, Apple, Google, Facebook, and Instagram have all rolled out features designed to help us form healthier relationships with their products. These include the screen-time trackers I mentioned previously, as well as app timers, distraction blockers, and tools to help us unplug and sleep better at night. But given that these brands all have a clear interest in keeping us hooked on their offerings, the intent driving the initiatives is rightfully fraught with consumer skepticism. Is it all a big, superficial PR scheme, or could these tools actually help us combat tech addiction?

The roots of our unhealthy relationships with our phones, explained

One of the main reasons it’s so hard for us to just put down our phones is the addictive nature of games, social media, and the devices themselves. Think about it: You tell yourself you’re just going to take a quick peek at your BFFs’ Insta Stories before you go to bed, and 45 minutes later, you’re feverishly double-tapping @tindernightmares posts from six months ago and can’t. pull. yourself. away.

Indeed, technology can be as addictive as drugs or gambling, says Kristina Hallett, PhD, a board-certified clinical psychologist and executive coach. It all comes down to a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which is released into our brains when we do something that we expect will yield a reward. “One of the ways dopamine is released is when we have positive social connections, [and] much of our screen-time usage is related to social connections,” Dr. Hallett says. “So a Facebook like or an Instagram share equals a shot of dopamine.”

What’s more is these devices and apps are programmed to stimulate our reward pathways to keep us coming back, just like a casino game might. One example: Have you ever noticed that sometimes your Instagram “like” notifications are delayed, appearing on your screen in a batch several hours after they actually happened? This is intentional—just like getting triple sevens on a slot machine after an hour of bad luck, receiving multiple notifications after a period of silence can lead to a bigger dopamine hit, says neuroscientist and AI expert Ramsay Brown. “They’re holding some of them back for you to let you know later in a big burst. Like, hey, here’s the 30 likes we didn’t mention from a little while ago,” he told 60 Minutes. “Why that moment? There’s some algorithm somewhere that predicted, hey, for this user right now who is experimental subject 79B3 in experiment 231, we think we can see an improvement in his behavior if you give it to him in this burst instead of that burst.”

“Taking a break from social media, messaging, or email can prompt feelings of anxiety and concern that we are missing the most important interactions.”—Kristina Hallett, PhD, clinical psychologist

Dopamine’s not the only chemical that’s keeping us hooked on our devices. Cortisol, commonly known as the “stress hormone,” also plays a role. Researchers at Iowa State University have pinpointed a condition called nomophobia (“no mobile phone phobia”—seriously), which describes that feeling of stress that can occur when we’re separated from technology for too long. Nomophobia actually encompasses several phobias in one: the fear of not being able to connect with people, of losing our connectedness, of not being able to access information, and of being inconvenienced. It’s essentially FOMO in overdrive, says Dr. Hallett. “Taking a break from social media, messaging, or email can prompt feelings of anxiety and concern that we are missing the most important interactions,” she says.

Google’s research exposed that nomophobia can also encompass the sense of duty people feel to always be accessible. “When a person sends a text to someone, the sender expects that the recipient should respond immediately,” says Stanphill. “And the receiver, in turn, feels equally compelled to respond right away.” (The men I date seem to be mysteriously excluded from this, but that’s a different article.)

With all this in mind, it’s no wonder that the big tech companies’ motives have been heavily criticized in recent years, sometimes from people within their own ranks. Back in 2017, Facebook’s former vice president for user growth, Chamath Palihapitiya, was widely quoted as saying dopamine-driven tech tools are “destroying how society works.” Another well-known dissenter is former Google product manager Tristan Harris, who left his post as the brand’s Design Ethicist to form the Center for Humane Technology, spreading awareness of how technology “hijacks our minds and society.” And, perhaps unsurprisingly at the perfect time, tech companies are responding by giving us tools designed to help us be more mindful about our digital habits.

The “digital wellness” revolution

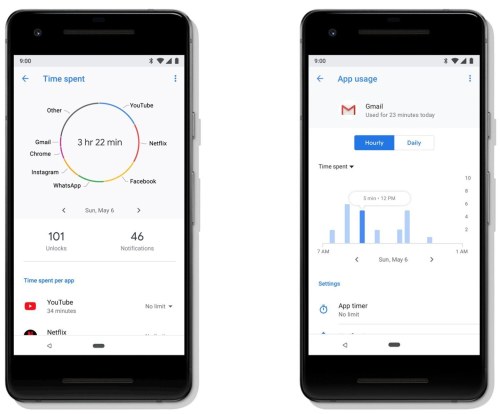

If you want to know exactly how you’re spending time on your phone, there’s now no shortage of ways to do so. (Although, let me warn you—you might not like what you see.) Android and iOS phones now provide detailed breakdowns of the number of times you pick up your phone, which apps you use most often, and how much time you spend on them. Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube have similar, albeit simpler, dashboards charting the amount of time you spent on each app. (They’re not front and center, however—to access them, you need to manually go into “Settings” for Facebook and Instagram or “Account” for YouTube.)

All five options allow you to set daily time limits for app use and to turn off notifications. On iOS and Android phones, you can also block out certain apps altogether for specified periods of time, like during work hours or at night. And both companies are also purportedly trying to help us get better sleep. As a rather roundabout way of combatting insomnia-fueled scroll sessions, Apple’s Night Shift and Google’s Night Light reduce the snooze-disrupting blue light emanating from their screens. Android also has a Wind Down feature, which turns your screen to unappealing black-and-white and automatically mutes all sounds before bedtime. Google Assistant takes sleep tech a step further with its Bedtime Routine, which can dim the lights in your house, set your alarm, lower your music, and turn on your phone’s Do Not Disturb.

Entertainment and social media companies are also working to improve the quality of the time we spend on their platforms—an important measure, given that research shows actively interacting on social media with people we know leads to improvements in well-being, while passively scrolling leads people to feel worse). For instance, Facebook updated its algorithm last year to put posts from close friends and family at the top of users’ feeds. Another study linked higher rates of “liking” and posting status updates with lower levels of mental health, which might explain why some platforms are rethinking the infinite scroll with added features like that “You’re all caught up” message Facebook and Instagram serve once you’ve seen all of the posts from the past 48 hours. Furthermore, YouTube now gives users the option to turn off its autoplay feature, which automatically starts a new video when the one you’re watching ends.

Okay, but are digital wellness tools actually helpful?

Here’s the thing: Although these initiatives all sound positive, it’s hard to say whether they’re really helping us, since the tech companies generally don’t share intel about results and habit shifts. I got the most information from Google. Although Stanphill wasn’t able to share any hard data about how Google’s Digital Wellbeing suite is impacting behavior or how many people are actively using it, she says there’s “an early indication that app timers correlate with decreased usage; this is a good sign that by raising awareness of this behavior, users are exerting more self-control.” Facebook and Instagram weren’t able to share any data or insights on this front, while Apple didn’t respond to my request for comment.

Psychologists Andy Przybylski, PhD, and Peter Etchells, PhD, would likely say the secrecy is unfortunate, given their argument that handing that information over to independent scientists would paint a clearer picture of the initiatives’ efficacy. “They superficially might seem well-intentioned, but without an independent assessment of how these apps are implemented, or what sort of information they gather, it’s impossible to tell whether they’re a genuine force for good for our health, or simply a marketing gimmick cynically designed to defuse the moral panic around screens and technology addiction that we currently find ourselves gripped in,” the pair recently wrote.

But that’s not to say we should automatically write off the initiatives. From a behavioral science perspective, says Dr. Hallett, the knowledge provided by screen-time trackers is powerful—especially when it comes to habits as ingrained in our routines as checking our phones. “It’s similar to a food journal,” she says. “One of the first steps in creating a healthy lifestyle and relationship with food is having the data regarding what and how much you are eating. This is just as true with screen time apps. People are often very surprised to learn exactly how much time they have spent on their device. Having the specific knowledge enables the individual to make a conscious decision to behave differently.”

“Like most trackers or apps, usage [may] go down because of feelings of guilt for not performing how we want.” —Jess Davis, tech ethicist and founder of Folk Rebellion

Jess Davis, tech ethicist and founder of Folk Rebellion, a media company focused on unplugging, agrees that when we’re given tools that encourage us to unplug, we may end up feeling a sense of permission to spend less time on our devices. “Believe it or not, people are still at the entry point of ‘Wait—I don’t need to always have my phone on me?'” she says. But she’s not sure if these tools will result in lasting change. “Like most trackers or apps, usage [may] go down because of feelings of guilt for not performing how we want,” she says.

This is definitely the case for me. After several consecutive weeks of cringing at my Sunday Screen Time notifications, I decided to put a 15-minute daily time limit on my social media use. However, I never actually stick to it. When my 15 minutes are up, I have the option to turn off the time limit or extend it by another 15 minutes, which I inevitably do. And at this point, I automatically ignore the timer whenever I see it. (I fared a lot better when I tested out a Google Pixel phone for this story, as its app timers locked me out of social media for the rest of the day once I reached my limit.)

But there could be another way that my Screen Time program may benefit me. Dr. Hallett says controlled social media breaks can actually be good for productivity, and that app timers can create a container for this. “Research in the field of peak performance demonstrates that breaks are vital to achieving the highest level of performance. This research holds true across professions, and is also good life advice,” she says. “So planning a timed break for social media use or connection can be a good choice, and the screen-time apps provide a simple way to implement this.” (Not all experts agree that social media is the best way to fill your time during a break, however—author Daniel H. Pink, for one, believes it’s best to aim for total disconnection when you’re taking a time-out from work.)

How to use screen-time data to your advantage

If you’re concerned about your usage, Dr. Hallett recommends turning off notifications and limiting your social media and email use to specific times during the day. Another option, per the Center for Humane Technology, is to remove the apps you’re most worried about from your home screen. This means you’ll only be able to access them by typing the app name into the search field—an extra bit of effort that may dissuade you from launching them in the first place. The organization’s also a fan of voice memos and “quick reactions” in texts (like the thumbs-up or “ha ha” icons you can reply with in iOS), as they allow you to get in and out of messaging apps more quickly. Voice tools like Alexa or Google Home can also be helpful, as they allow us to, say, play a song or call someone without picking up our phones (and potentially getting sucked into an unrelated activity.)

“The truth of the matter is that most of us are addicted not just to the tech itself, but the busyness as well. For society to change its habit, it will have to start in offices, businesses, and corporations.” —Davies

Davis feels the responsibility for combating tech overuse shouldn’t just lie with individuals and tech companies, though. Workplaces, too, need to start re-examining their policies so people feel more comfortable powering down at the end of the day. “Since most businesses operate in clouds, around computers, and communicate predominantly digitally, it’s imperative that companies start to think about their role in digital wellness,” she says. “The truth of the matter is that most of us are addicted not just to the tech itself, but the busyness as well. For society to change its habit, it will have to start in offices, businesses, and corporations.” In an effort to combat digital burnout, she’s been helping companies set up codes of conduct around teams’ digital communications. “It’s amazing to see what happens to productivity when a company gives its most valuable assets—its employees—time to unplug and be present with themselves outside of work,” she says.

If none of this works and you’re noticing symptoms of serious technology addiction—like your phone use is interfering with your job performance and/or social life, or if you’re feeling anxiety, depression, defensiveness, or guilt regarding your digital habits—it’d be wise to seek the help of a mental health professional. But if you’re simply looking to create awareness about and set guidelines for your phone use, the available tools can be a positive place to start. “We don’t need to throw our devices away, but we do better when our devices work for us, rather than against us,” says Dr. Hallett. And even if they stress me out, I suppose my weekly screen-time alerts really are helping my device work for me, just as they should.

Women who work extra-long hours are more prone to depressive symptoms. That’s a pretty good argument for taking email off your phone—here’s what happened when one CEO tried it.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.