What This Lifting Influencer Wants You to Know About Strength, Diet Culture, and Gymtimidation

Because sometimes we need a little nudge to step out of our comfort zone.

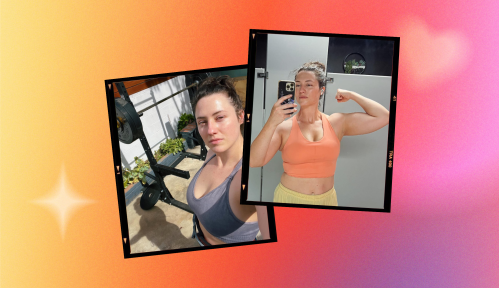

Casey Johnston doesn’t pretend that she got into lifting weights to get strong, or to feel empowered. In her new book, A Physical Education: How I Escaped Diet Cultured and Gained the Power of Lifting, she’s honest about the fact that, at first, it was another diet culture-fueled attempt to lose weight, after cardio and dieting kept failing her.

But that didn’t last long. Soon, Johnston fell in love with lifting—with how it made her feel, with how it made picking up a box of cat litter easier, and with how it changed her relationship with her body from animosity to curiosity. Lifting gave Johnston a pathway to reject diet culture altogether, and the strength to leave a toxic relationship and a toxic job. It also gave her a career: For years, she wrote the “Ask A Swole Woman” column in The Hairpin, SELF and Vice, and now she authors the popular She’s a Beast newsletter.

In A Physical Education, she interweaves her personal journey with the latest research on dieting, strength training and health to powerful effect. Well + Good spoke to her about her book, the lifting myths that still persist, and her advice for women who are intimidated by lifting.

W+G: Since you started lifting in 2014, how have you seen cultural attitudes around it change?

Johnston: When I got into lifting, it was still a super macho, alpha bro thing to do. It was something that you do if you are shallow, but also maybe have an aggression problem. Now, there's been a lot of forces that have come together to allow a greater diversity of people to get into it. I think I've been a part of this, but also benefited from it. There’s also been more discussion of the benefits that lifting has, not just for young men, but for everybody—older people, women. I think the internet's been a big force, and there's been a democratization of access to the information that you need. It used to be that you needed to ask a gym bro to spot you and evaluate your form and just hope that guy was not going to make everything worse. That's still true to some extent, but I think there’s greater access to information, and more of an emphasis on the things that allow us to lift for the long term and lift for health, like form and a balanced workout schedule.

W+G: It feels like we are aware as a culture of the psychological toll of diet culture. In the book, you talk a lot about the physical toll, which is less known. Why do you think that is?

Johnston: Because it undermines the whole thing so significantly if we know that dieting is a vicious cycle that will only make it harder for you. Dieting, the way most people do it, depletes your muscle mass, which depletes your overall physical well being, as well as your metabolism and the systems that allow you to maintain your biological equilibrium. Because of that, you are likely to gain the weight back as body fat, and it becomes this slow exchange of body mass. It’s not only yo-yoing, which was the term when I was growing up, but going down these stairs of destruction to your body composition.

There's also more research coming out showing that the role of weight in our health has been vastly overstated. Not only is weight not the main marker of health, it's really not a good one. People have been saying this for a while, but now science is bearing it out. A lot of this stuff is common knowledge in the lifting world, but it's not in the regular world. We know that maintaining a low body fat is not good for you. It is not comfortable. It really sucks. Your sex drive crashes. You can't think straight, you can't sleep, you're miserable.

W+G: Are there myths or misconceptions around lifting that you still hear?

Johnston: I still hear people worried about getting bulky lifting weights. If you wanted to get bulky, lifting weights is how you would do it. But it takes years and years and deliberate, specific daily effort and a whole workout program designed around that purpose, in order to make that happen. Most people gain muscle and strength very slowly, at the rate of, like, a pound per month.

There's so many other physical activities and sports that have built up fear around that, so it's understandable that people are afraid of it, but it's not the truth.

The other thing is that people are fearful of the potential for injury. They're like, my knees already hurt. My back already hurts. We have this perception that lifting is this super intense thing that already strong people do, whereas the real way that lifting works is that it's super adaptable to where you're at. You're supposed to do what is sufficiently challenging for you and your current ability level. There is a focus on how you do it; that it's not supposed to hurt and that it is really supposed to help facilitate performing daily physical functions in a way that is less harmful to your body. Your knees might hurt and your back might hurt because you pick things up and bend over in a way that puts unnecessary strain on your joints. Lifting can teach you to pick up things and bend over using your muscles. In that way, not only is it not gonna ruin your knees to squat or ruin your back to deadlift, but it can appreciably make it better.

W+G: You talk a lot in the book about how lifting became not just about getting stronger, but about getting to know yourself better. What was it about lifting that allowed you this self-discovery?

Johnston: Lifting weights was this kind of isolated sandbox that encouraged me to do one incremental thing, like a rep or a set, and then to take a pause and rest and say, How did that feel? Was it too light? Was it too heavy? How was your form? That encouraged this practice of self inquiry for me that I'd never had. I never thought about how anything made me feel. I had an alcoholic father and my mother had her own challenges. That really drilled into me that I had to always stay responsive to everybody else, watching and waiting for cues and instructions. I couldn't be thinking about how I felt because I was trying to protect myself, and that is a classic way of becoming somebody who always needs to push their feelings down for safety's sake. So having this activity with that practice of self inquiry expanded outward into my life in the best way.

W+G: In the book, there’s a pivotal moment when you walk into the lifting gym for the first time, despite being intimidated. What advice do you give to other women who are intimidated by those spaces?

Johnston: Yeah, it was very intimidating. It was very crowded and loud and all the equipment was packed together—you were kind of stepping over somebody all the time to get to where you needed to go. What I tell people now is that to conflate the goal of accomplishing a workout with getting used to the gym as someplace new is a mistake. Separate those two things. Make a time, before you intend to go work out, that you go to the gym, just to get used to it. Go on a cardio machine where you can see the rest of the gym and watch everyone else and see what they do. How do people interact? How do they ask each other for equipment? How do they adjust the squat rack? Where do they stand when they’re doing dumbbell stuff? It’s like getting used to a new workplace, and they’re like, we don’t have your computer ready yet, but you can sit at your desk. That’s time you actually do need to familiarize yourself.

W+G: One reason why some people are resistant to lifting is that it doesn’t always feel like you’re getting a “good workout”—you may not break a sweat, it doesn’t take very long, you may not feel depleted in the same way you do after cardio. How can we rewire our expectations around what exercise is supposed to feel like?

Johnston: It's tough because exercise has become so entwined with our value of always working really hard. It's like, if anything is comfortable, you're not working hard enough, you're not trying hard enough, you're being lazy. You'll hear “no pain, no gain,” and “sweat is your fat crying” and trainers telling you to push, push, push, push. We have a sense that if we're putting in any effort, it needs to be for some higher goal or accomplishment, instead of facilitating our own experience of life and ourselves. I think people who feel compelled to exercise will tell you they're doing it because they feel like they have to, or because they feel like they need to be attractive, rather than it being something that we can enjoy, and that is centered around inhabiting the only body that we have and having a relationship with that body. Our physical experience of the world is one of the things that we're theoretically here on Earth for, and we are allowed to have a relationship with ourselves that is not based on what our body is doing for everyone else.