Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

How Hair Care Became a Father-Daughter Ritual that Helped Affirm My Identity

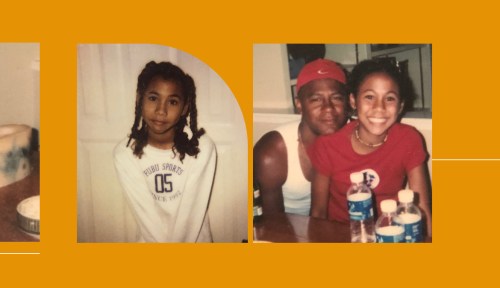

Hair care and identity became linked for one writer, who found connection with her father through him braiding her hair.

When you are young, female, and Black, you get used to the feeling of other people’s hands in your hair. Sometimes it’s the hand of an auntie, stroking your spiral strands at a family gathering, asking if you’ve been a good girl. Other times, it’s the wandering hand of a white transgressor, reaching out to pluck a curl because they “just want to know what it feels like.” Occasionally, you get clumsy hands, or hands that don’t know their way around Black hair. You tolerate more than you should and relish in the moments when your hair is in the hands of someone skillful, someone adept at navigating your tangled, beautiful maze.

For me, this person was my father.

My dad is about as macho as they come. He’s a brawny, athletic, beer-drinking man whose hands know how to handle a basketball and the kinkiest of curls. Raised in a household with 10 siblings, my dad learned the art of styling Black hair from the many afternoons he spent playing with his sisters and their dolls. Back then, he only needed a miniature comb and some rubber bands to achieve the hairstyles he wanted on the dolls—nothing like the assortment of products that would become a part of his arsenal when he had daughters of his own.

Every morning between first and fourth grade, I sat on the floor of our living room next to a pile of rubber bands, a spray bottle, and a jar of Blue Magic, which we simply called “grease,” while my dad worked his way through my hair. He’d take handfuls of Blue Magic, shimmering like an indigo galaxy, and rake it through my hair, tugging my little head from side to side as he combed, parted, and braided. Some days, he’d divide my hair into six sections, slather a glob of grease into each one, and then twist my curls in his hands over and over until my hair held the shape of a perfect ringlet when freed. For a while, this was my favorite hairstyle.

While my dad worked on my hair, my two younger sisters would usually be in the back with my mom, getting dressed and waiting their turn with Dad. My Filipina mother didn’t know how to navigate our curls in the way my dad did, what with her slick, tangle-free hair—so she took care of other parts of our morning routine like picking out clothes and making breakfast.

I didn’t know it at the time, but my dad was enacting a tradition each morning that he sat down to do my hair, one that I would forget and then recall years later in my quest to practice better self-love towards myself.

Our ritual continued this way until fifth grade when I decided I wanted to wear my hair like my white friends. As a brown girl living in the suburbs of Reno, Nevada, I was largely surrounded by white people: They were my friends, classmates, teachers, and crushes. For me, fitting in wasn’t just about having the newest Skechers, it was also about having a persona of whiteness. So I started being pickier about the hairstyles my dad was sending me to school with. I made requests for less elaborate braid-work and asked him to try half-up, half-down styles. Some days he’d listen, some days he wouldn’t.

On the days that he didn’t, I’d let him grease, braid, twist, and tie my hair however he insisted. But once I was at school, I’d go straight to the bathroom where I’d undo all of his handiwork, ripping apart braids and combing my fingers through spirals before tossing my hair into a messy bun. Undoing my hair happened quickly, in a few hot breaths with small, determined fingers. I didn’t know it then, but I was learning the act of undoing, not only against my curls, but against my Blackness. I’d forbid both to exist in their natural states for years and years to come.

By my freshman year of high school, I was straightening my hair constantly. Much to my father’s disappointment, the flatiron had become a permanent fixture in our bathroom, and I rarely left the house without running it through my curls. Despite my resolve in pursuing sleek, straight hair, my dad never missed an opportunity to plea for me to wear my hair curly, or to tell me how beautiful my natural hair was.

“You’ve got some of the most beautiful hair out there,” he’d say.

It took years for my dad’s words to really reach me. It took moving away from home, writing a thesis on my racial identity, and reckoning with a lifetime of subduing my Blackness for his words to finally sink in. When they did, they were transformative.

It’s been over 20 years since I last sat down on that shaggy carpet and let my dad style my hair. In that time, I’ve pressed, flattened, smoothed, and straightened my hair by just about any means possible. It’s only been in the last few years that I’ve begun to coax my curls back to life. I’ve purchased all new products and watched a thousand curly hair tutorials, practiced natural styles, and adopted a nourishing hair-care routine.

Most importantly, I’ve meditated on the hair-care ritual of my childhood. I’ve thought of my dad and the way his loving hands worked through my curls, as if they knew they were holding something precious. I made a vow to approach my curls with the same loving care. In doing so, I’ve begun to embrace and embody my Blackness.

What my father was showing me all those years ago was a way to nurture a part of myself that was distinctly Black, to bring it to life, both beautifully and unapologetically. I didn’t know it at the time, but my dad was enacting a tradition each morning that he sat down to do my hair, one that I would forget and then recall years later in my quest to practice better self-love towards myself—all parts of myself.

Oh hi! You look like someone who loves free workouts, discounts for cult-fave wellness brands, and exclusive Well+Good content. Sign up for Well+, our online community of wellness insiders, and unlock your rewards instantly.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.