Historically, ‘Radical’ Groups Have Often Positively Impacted the State of Wellness and Health in the U.S.

The Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and others served their communities to ensure basic human needs were met. This is how they made mandated wellness.

In the 1970s, the South Bronx was the heroin capital of the world. At the time, heroin-related incidences claimed the lives of more adolescents, largely Black and Puerto Rican, than any other cause. Witnessing the drug crisis in their poor communities and the government’s disregard of their plight, revolutionary groups like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords used bold tactics to support the underserved population. On November 11, 1970, they joined forces to stage a historic sit-in at the notorious Lincoln Hospital that ultimately pressured officials to open an inpatient drug-treatment program. Lincoln Detox, as the clinic was called, was the first of its kind, offering holistic drug rehabilitation that employed complementary medical treatments like acupuncture and offered patients a political and social education that drew connections between capitalism, heroin, and genocide. The militant action is just one example of the lasting contributions that revolutionary groups of the era made to public health.

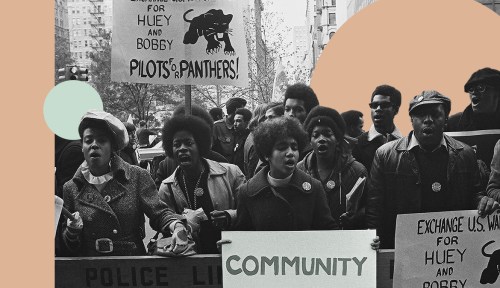

While ’70s-era activists are often remembered as radical gun-carrying, black-leather-clad, beret-donning “hate groups” that “threatened” U.S. security, these predominantly youth-led political organizations, including the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and the United Farm Workers (UFW), as well as women’s groups and several other organizations allied with the New Left, served their communities by fighting to reclaim the dignity of the downtrodden and working to ensure their basic human needs were met. Within destitute inner-city neighborhoods—where buildings were dilapidated and infested with rats, illnesses were prevalent, laborers worked with injuries, and addiction touched many families—freedom fighters also became leaders in community health and wellness.

These ’70s-era activists emerged out of the changing times of the ’60s. In The Young Lords: A Radical History, author and historian Johanna Fernández describes the 1960s as a time of significant medical transformation. The federal government began retreating from funding public goods, leading to the rise of a dominant for-profit health system that discriminated against low-income communities of color and used them as guinea pigs for unethical medical experiments. “Poor people of color came to be treated not as consumers of medical services but as this exploitable commodity, and they were subjected to all these for-profit medical practices: medical tests, prescriptions, and procedures,” says Fernández.

Children growing up in the early ’60s who accompanied elders to hospital visits—and, in the case of Spanish-speaking families, were often called on to serve as language and cultural interpreters for relatives and neighbors—directly witnessed and experienced the indignity of these inhospitable medical institutions, Fernández says. As these children became teens and young adults, they didn’t forget the discrimination they endured while waiting long waiting hours to receive inadequate care. “There was growing recognition that people’s health was in trouble and that the access to health services was inadequate,” says Mary T. Bassett, MD, the director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University.

The Black Panther Party as Health Activists

In 1966 in Oakland, California, college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton founded the Black Panther Party to challenge police brutality and keep their communities safe from violence. The group was in a position to assist Black neighborhoods that were underserved by medical institutions and vulnerable to their harm, according to Dr. Bassett. With 5,000 members and 38 nationwide chapters by 1968, the Black Panthers had people power and a shared vision to “serve the people, body and soul.” The group accomplished this with various so-called survival programs aimed at tackling the sources of poor health: poverty, hunger, unemployment, homelessness, and inadequate education. Among its initiatives was a free breakfast for children program—which fed tens of thousands of hungry youth and inspired the creation of today’s federal school breakfast program—as well as services like clothing distribution, lessons on self-defense and first aid, classes on politics and economics, and an emergency-response ambulance team.

By 1972, the Black Panthers also had national free health clinics staffed by volunteer doctors, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, some of whom were former members of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, a group of U.S. health-care professionals that organized in 1964 to provide services for civil rights workers and community activists. Later, when the Black Panthers learned that sickle cell anemia was a neglected genetic disease that disproportionately affected people of African descent, they created their own homemade rapid screening test and began testing community members at clinics and through home visits. That year, the party officially added health to its Ten-Point Program, stating in its sixth point that the organization wants “completely free health care for all Black and oppressed people.”

In Boston, Dr. Bassett, then a college student, volunteered at the party’s Franklin Lynch Peoples’ Free Health Center, which was named after a young man who was reportedly killed by a police officer while in hospital care. There, she scheduled doctors for staff clinic hours and eventually ran the chapter’s sickle cell screening program. “It was a health service, but it also was a form of community organizing. It was showing how people can work collectively to achieve things that they can’t do separately,” Dr. Bassett says.

The Young Lords Influence on Patients’ Rights

The Young Lords, a Chicago-gang-turned-revolutionary-group of Puerto Ricans and Black Americans with chapters across the country, were in a similar position to help improve the well-being of their communities. Collaborating with other social justice and medical organizations, the group aimed to tackle “diseases of poverty,” a term they adopted from the Cuban Revolution that refers to the pervasive and preventable diseases caused by impoverishment, including poor nutrition, drug addiction, asthma, lead poisoning, tuberculosis, diabetes, hypertension, and mental health illnesses like depression and anxiety.

The group of teens and young 20-somethings conducted several operations that helped lead to reforms. In Chicago, members followed the model laid out by the Black Panthers and tackled food insecurity with grocery giveaways and a free breakfast program. Additionally, the Young Lords established a free clinic that included a dental program as well as education on health and nutrition. In New York City, it initiated free food programs, provided political education with its Palante newspaper and weekly radio show on WBAI, and recruited members to escort children to school safely. Moreover, they organized famously gutsy actions that served the community with preventative care and forced an otherwise negligent government to take notice and start heeding the needs of marginalized communities.

During the fall of 1969, the New York chapter of the Young Lords created a Ten-Point Health Program and Platform that demanded free health care, door-to-door preventative health services, and health education. That same year, they embarked on one of their most consequential campaigns: the Lead Offensive.

In the city, the threat of lead contamination, which could lead to irreversible brain damage or death in children, was known for decades. Despite the peril, the local government had been sitting on tens of thousands of lead-screening tests. After several meetings failed to convince officials to utilize the tests, the members staged sit-ins demanding that they be given 200 lead-testing kits. The operation was a success. The following day, the Young Lords began administering door-to-door screenings. Later, in 1974, the Journal of Public Health credited the Young Lords’ campaigns with the passage of the first-ever anti-lead poisoning legislation in New York City and the formation of the Bureau of Lead Poisoning Control.

In 1970, the Young Lords organized other effective attention-grabbing offensives. That June, members hijacked the New York Tuberculosis Association’s mobile clinic and parked it in Spanish Harlem, where they offered 24-hour testing to laborers who weren’t able to get tested during the truck’s normal limited hours of operation. In July, they occupied the Bronx’s rundown Lincoln Hospital, a teaching site for medical students where patients were treated more like guinea pigs than humans in need of medical treatment. During the takeover, they protested the city’s indifference to their health needs and, with the help of the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement (HRUM) and the Think Lincoln Committee (TLC), they instituted community programs in the auditorium, including a free provisional screening clinic for anemia, lead poisoning, iron deficiency, and tuberculosis, and established a daycare center and classroom for political and health education in the basement.

Not long after the action, Carmen Rodriguez, a mother with rheumatic heart disease, died after an unsupervised resident failed to read her chart and administered a saline-based abortion, which is fatal for people with heart diseases. Her case, which marked the first death that occurred after New York State had legalized abortion, stirred freedom fighters to demand a public clinical conference. There, community members laid out their grievances, pressured the head of Obstetrics and Gynecology to resign, and inspired medical personnel to strike and temporarily close the OB/GYN department.

The actions of the Black Panthers and Young Lords were “dramatic, impactful, and successful,” says Cleo Silvers, a former member of both groups who participated in several of the high-profile offensives in New York.

For those who know Silvers, she is described similarly. In 1970, following the takeover of Lincoln Hospital, she co-authored a set of demands aimed to establish a protocol of communication between patients and doctors that would decrease the likelihood of tragedy and empower patients to make informed decisions about their care and be treated with dignity and respect. The orders, known as the Patient Bill of Rights, have since been adopted by hospitals across the country.

“City Hall and hospital administrators pretended like we didn’t know what we were talking about, but they always watched and listened,” she says. “As a result, the Patient Bill of Rights, significantly watered down, is on the wall in every hospital room and in every hospital in this country.”

Following the death of Rodriguez, the women of the Young Lords, a growing segment of the organization, produced a Position Paper on Women that offered a new-wave feminist perspective and vision. The paper looked at the layered oppression of low-income women of color, emphasizing experiences of sexism and gender roles but also tackling women’s health issues. It supported a women’s right to affordable and safe abortion care and condemned the sterilization of women in Puerto Rico without their informed consent, a practice that had been occurring on the island for decades through a government-sponsored program with ties to the eugenics movement.

“The case of Carmen Rodriguez shows us that the right to an abortion is not enough, because if you are poor and Black or poor and brown, you don’t have access to good care,” says Iris Morales, the Young Lord’s former deputy minister of education and co-founder of its Women’s Caucus. “We said that we want abortion accessible and we want quality care. It was a revolutionary take at that time, especially among nationalist groups.”

The United Farm Workers’ Movement to Improve Health Care

On the West Coast, the United Farm Workers (UFW), headed by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, were also influencing health care. At the time, farmworkers, exploited by growers and large corporations, worked under deplorable conditions with little-to-no protections. Founded in 1962, UFW was the first labor union for farmworkers in the country. Teaming up with other organizations, most famously the Filipino-led Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, they assembled several nonviolent strikes, boycotts, marches, and fasts that ushered their cause to a national audience and achieved collective bargaining rights for farmworkers that improved wages and working conditions.

As farm work was, and remains, one of the most dangerous occupations in the U.S.—with hazardous pesticides and farm equipment leading to illnesses, injuries, and death—health was an early priority in the dozens of union contracts it would make with growers. Kathy Murguia, a mental health clinician and former UFW organizer, offers one example of what could happen without such a contract: “My husband lost his fingers on his left hand in an industrial accident,” she says. “He was working in cotton, and somebody turned on the gin while he was cleaning it. It sliced off his fingers.” According to Murguia, the company that her husband worked for offered a settlement of $5,000, hoping he would “disappear” and the whole case would just “go away.”

As a laborer and activist, Murguia often witnessed and heard similar stories. There was the mother she worked with at a packing shed who was sent home—and never heard or seen again—after her son was injured while working in apricot production during an incident at the facility. There were the field workers who were poisoned, fell ill and, in some cases, died after planes dropped clouds of hazardous pesticides and herbicides on the land.

And then, in 1966, there was the death of Rodrigo Terronez. A vice president of the UFW, Terronez fell off the back of a truck, causing a skull injury. When the nearby Delano Regional Medical Center was unwilling to accept Terronez as a patient, he had to be driven 45 miles away to Kern County General Hospital. Before he made it, Terronez died in the vehicle, fatally choking on his own blood.

Considering the dire health needs of laborers and organizers, the UFW opened several medical clinics, staffed by volunteer nurses and physicians, and created the Robert F. Kennedy Medical Plan. While they established clinics throughout California, the most popular was the Rodrigo Terronez Memorial Clinic at the farmworker group’s complex near Delano. There, laborers and organizers underwent a screening evaluation and had access to the clinic’s ambulatory services; pediatric, medical, surgical, and OBGYN care; as well as laboratory work, X-rays, social services, and counseling.

“From the very beginning, the concern for health [within the union] was there because it was such an obvious need,” says Murguia, who oversaw the clinics as the Director of the National Farmworker Health Group.

Thanks to the daring activism of the UFW, the health plight of farmworkers was covered in mainstream outlets like The New York Times and The Nation, helping the union to enact legislation and protective measures regarding the use of pesticides and to secure contracts that included medical insurance along with health and safety clauses.

How ‘Radical’ Groups Brought Wellness to the Mainstream

While advocating for changes in health care, many of these revolutionary groups also practiced personal and community wellness. According to Murguia, Chavez often educated farmworkers about their diets. For him, it was just as important to fast for the movement as it was to consume nutritious food to help his body recover. A vegetarian, he regularly juiced, drank tea, and used natural medicines passed down to him by his mother. He also studied and practiced acupuncture and acupressure, offering these services to haggard workers and encouraging them to join him in stretches and yoga. Similarly, Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Black Panthers’ Illinois chapter, was an early promoter of wellness ideas. A leader in the Party’s free breakfast program, he often educated the community about food production, healthy eating habits, and the effects of poor nutrition. And Morales says the Young Lords produced a paper on nutrition, and the organization’s cook, Julio Roldan, made an effort to prepare balanced dishes that were nutrient-dense during communal meals.

Some of the revolutionary groups were also intentional about providing spaces within the movement that supported the mental, physical, and spiritual well-being of members. For example, the Young Lords had a temporary staff ministry that helped people who were kicked out of their homes find housing, assisted unemployed individuals in securing paid opportunities, helped members work through relationship issues using mediation, and provided safe and confidential spaces members could go regardless of the trouble they were experiencing. “We weren’t therapists by any stretch of the imagination, but we tried to be helpful and provide options and ways in which members could be supported,” says Gloria Rodriguez, who was a part of the three-person ministry.

According to Rodriguez, creating spaces where young people could unlearn machismo culture (aka the pressures of perceived masculinity), decolonize their thinking, open up about their past and ongoing trauma, and find solutions to their quandaries, helped to establish a sense of family and trust that was essential to the organization. “With the work that we were doing, and the surveillance we experienced, we had to trust each other with our lives—and it was a way we could do that,” says Rodriguez, who went on to work in wellness.

Beyond their community health activism and their work to establish organizational wellness practices and spaces, the revolutionary groups of the ’60s and ’70s also understood that political education, fighting in the streets, and engendering reforms and services for their communities were inherently therapeutic and empowering. “Part of being a healthy human being is reclaiming your dignity,” says Dr. Bassett. “To stand and fight is an act of self-preservation and an act of reclaiming one’s health.”

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.