Our editors independently select these products. Making a purchase through our links may earn Well+Good a commission

What would happen if every doctor started meditating?

Well+Good Council member Drew Ramsey, MD, Dr. Drew Ramsey talks with a med-school meditation trailblazer about this potential game-changer for public health.

The life of a physician is famously busy. Between long hours in med school, an often-grueling residency, and the pressure of being on-call as a professional, it’s hard to find a moment to breathe. And yet, that may be exactly what physicians need to thrive under such stress. That’s why Mark Gelula, PhD, president of the Board of Directors of the Zen Life and Meditation Center of Chicago, began teaching the practice to medical students at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2013, after joining the faculty as an assistant professor of medical education in 1995. His weekly drop-in class drew a following of high achievers looking to lower the inherent stress of medical school, an issue recently confirmed by the Journal of the American Medical Association. A 2016 study showed that a quarter of medical students across 47 countries are depressed, and 1 in 10 experiences suicidal thoughts.

Here, Well+Good Council member Drew Ramsey, MD, a practicing psychiatrist, speaks with Dr. Gelula (who is also the father of Well+Good co-founder Melisse Gelula) about the promise of meditation—and why the traditional medical establishment is finally catching on.

Dr. Ramsey: Well, should doctors meditate?

Dr. Gelula: Absolutely. I’m going to say, it’s the hardest thing for a physician to do, because it’s so opposite of the way they think they should be. One of the important reasons that a physician wants to meditate is because they need to be able to grab the moment, to separate themselves from the moment that they were in. To recognize the moment that they’re in now, and then step into the next moment and know that those aren’t the same moments. That’s how I learned to meditate.

So meditation will help me emotionally transition from patient to patient and health care encounter to health care encounter.And…it will help you in your daily life. It will give you moments of respite so that you’re ready to see your family, so that you’re not carrying everybody on your back. It’ll give you a moment to recognize how things are piling up and you’re beginning to get anxious, and that anxiety leads to more stress. This was one of the big issues that I dealt with medical students about: the difference between just meditating and meditating with a purpose of recognizing how they become more anxious.

“This is going to be the way physicians are trained in the future.”

What happens to them as you help them become more mindful and incorporate meditation into their lives?One of the things that I taught them is that a big part of meditation is breathing. So we spent a lot of time on breathing. I taught them that when they’re in the middle of a test, they have 35 to 40 seconds per question. There are some questions that aren’t going to take that long. They have plenty of time, so I’ve taught them to breathe when they can. Students will tell me that they get so panicked in the middle of a test, they forget everything. So I taught them a technique called STOP. S, stop. T, take a breath. O, observe what’s happening and breathe in that moment. P, proceed. The students tell me that that works phenomenally.

We love mnemonics in medical school.Right! Another time, I knew a first-year student who had trouble falling asleep. She was exhausted during the day, because she was only getting about four hours. So I said to her, “Why don’t you start meditating at night?” She tried it and began to fall asleep pretty quickly. After that, she found it was so powerful for her, she began meditating regularly. Then she started bringing friends to the course. Does meditation help? It must if people bring friends—and she wasn’t the only one who did that.

It feels to me there’s been an increased interest overall in medicine and some of these very sensible lifestyle factors like food, meditation, and mindfulness breathing. Do you think that we’re seeing the beginning of the change we all hope for?Yes. Actually, the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME), which is the accrediting body for medical schools, now requires some portion of the curriculum to focus on wellness. That means taking care of yourself physically and emotionally, and it can include things like emotional health. Within that area they typically include meditation, yoga, and psychotherapy that is meditation-related, like cognitive behavioral therapy.

Making sure we equip physicians with a set of skills to deal with the stressors that they’re about to encounter…Yes. Now the curriculums are changing because the LCME has said the traditional system of test, test, test isn’t working. Some of that is changing, but I think the focus on wellness is so broad that students are now recognizing the importance of it for every part of themselves—not just their lifestyle, but in seeing patients.

My patients who are physicians always tell me this: “The time that I need to meditate the most is when I’m stressed and busiest—and that is when I drop my practice.” What is your tip for them?In a lifestyle progression of the development of meditation skills, the number-one thing is first taking the time to do it and making it a habit. People don’t take the time. But there’s no quick and easy way to teach that.

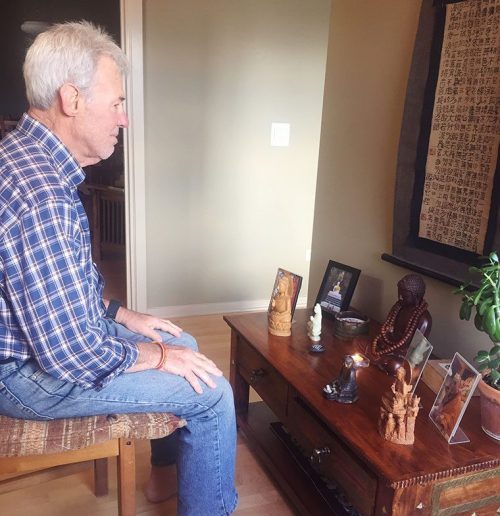

One of my favorite patients got somewhat addicted to meditation. He had a very busy mind, and after starting a regular meditation practice, he told me he began to crave it. Are some people just naturally better meditators than others?I think some people do take to it more readily than others. I think people who don’t like meditating, like my son, might say, “You know, I’ve tried it a few times but I don’t know.” I’ve said to him, “Are you meditating?” Because for a while he had a very stressful job. He said, “Yeah, I tried but I don’t have time and I’m really busy.” I think if it was really important to him and it was helping him, he would do it more. For some people, it takes longer to find that key.

We are in a world of immediate rewards and immediate gratification. What should we look for in terms of the signs that meditation is helping us? What do you think people begin to see?One of the first things that I think people notice is they begin to see themselves. They notice that things are building up. The second thing that I think people notice is how much clearer their breathing is. A third way that we know that people are benefiting from meditation is that they begin to be more perceptive.

“We’re all frightened of seeing our demons, seeing what’s inside us.”

I helped teach mind-body skills in a hospital in Indianapolis—everyone from the CEOs and trauma surgeons to ambulance drivers and food service workers. There was a lot of healing that needed to happen. What do you find that the health-care providers are frightened of?I don’t think they’re any different from any other human being. We’re all frightened of seeing our demons, seeing what’s inside us—and we spend our lives trying to escape it. I think the present state of our society right now is a great exploration of that phenomenon, sadly. But I think your question is good, and I’m going to turn it around a bit: How do we help people feel okay about being okay with themselves? Presuming that people are willing to meditate, then we have to help people have patience.

What does patience look like, specifically?It’s important to establish a habit of meditating for five minutes as frequently as possible. We know [regular meditation] will change the brain. Changes in the prefrontal cortex occur with that minimal amount of meditation.

Thank you for that permission, Mark, because I feel like it always gets framed as “20 minutes twice a day.” And when I say that to patients, they say they can’t.Exactly. But it’s good to lengthen that. If you can do it for 10 or 20 minutes a day eventually, that will provide significant, noticeable results. This is going to be the way physicians are trained in the future. The wellness of the physician is going to be an integral part of their own training. Of course, if they recognize their own wellness, then they’re going to be much better equipped to deal with the wellness of others.

As a psychiatrist and farmer, Dr. Drew Ramsey specializes in exploring the connection between food and brain health (i.e. how eating a nutrient-rich diet can balance moods, sharpen brain function, and improve mental health). When he’s not out in his fields growing his beloved brassica—you can read all about his love affair with the superfood in his book 50 Shades of Kale—or treating patients through his private practice in New York City, Dr. Ramsey is an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

As a psychiatrist and farmer, Dr. Drew Ramsey specializes in exploring the connection between food and brain health (i.e. how eating a nutrient-rich diet can balance moods, sharpen brain function, and improve mental health). When he’s not out in his fields growing his beloved brassica—you can read all about his love affair with the superfood in his book 50 Shades of Kale—or treating patients through his private practice in New York City, Dr. Ramsey is an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons.

What should Drew write about next? Send your questions and suggestions to [email protected].

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.