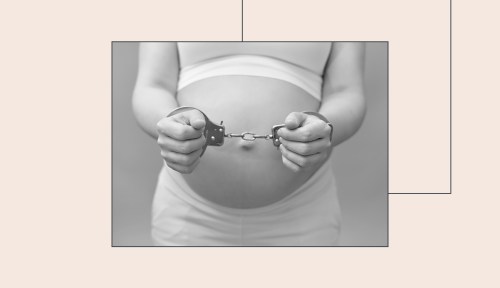

There Are No Standards of Care for Pregnant People in Prison, and That Needs To Change

If you want to know what pregnancy care in prison is like, listen to Pamela Winn, a former inmate who was kept shackled during her pregnancy.

If you want to understand what it’s like to be pregnant and in prison, look to Pamela Winn. A registered nurse in Atlanta, Georgia, she was in a federal holding facility in June 2008 waiting to learn her fate for a non-violent, white-collar offense. There, she took a pregnancy test: positive.

Experts in This Article

Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, is a medical anthropologist and Ob/Gyn at Johns Hopkins University.

Jamila Perritt, MD provides on the ground, community- based care focusing primarily on the intersection of sexual health, reproductive rights and social justice.

Winn was denied bond and kept in the holding facility when she was about six weeks pregnant. The first time she was being taken out of court, almost immediately after her positive pregnancy test, officers shackled her with a chain around her stomach. “I said to them, ‘You all know that I’m pregnant,’” Winn recounts.

Well into her pregnancy, Winn continued to experience shackling as well as solitary confinement for “medical observation,” which according to the ACLU is a common practice used for anything from isolating certain individuals for mental health concerns, to separating people who might have contagious infections, to a matter of convenience for corrections officers. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also points out that medical isolation during pregnancy can prevent people from accessing timely healthcare in an emergency situation.

One day, while shackled around her ankles, Winn fell while attempting to get into a van. Shortly thereafter, Winn noticed spotting. Drawing on her background as a surgical nurse, she flagged it as a sign of a potential miscarriage because of the hard fall, but the facility did not respond to her request for medical attention for two weeks. Even then, they dismissed her concern as a normal occurrence in early pregnancy. (Though spotting can occur early in pregnancy, it does warrant a check-in with an OB/GYN, particularly after a fall.)

Six weeks after Winn’s initial bleeding, the prison authorities agreed to take her to the local emergency room, since there was no obstetrician on-site to provide care. But the ER turned her away because the initial bleeding incident was too old to be considered an emergency. It took a series of weeks, and still she never got an accurate ultrasound reading or proper perinatal care to assess her pregnancy’s prognosis. While waiting another four weeks for approval to see an obstetrician for a follow-up, it was too late. In October 2008, Winn began experiencing more severe miscarriage symptoms at the holding facility—she was then taken to an ER and shackled to a hospital bed, where she endured the remainder of her pregnancy loss, as two male officers stood at the foot of the bed, in between her legs.

She was then taken to an ER and shackled to a hospital bed, where she endured the remainder of her pregnancy loss, as two male officers stood at the foot of the bed, in between her legs.

Why shackling during pregnancy and birth still takes place

As of January 2021, there were 17 states without any regulations limiting or prohibiting shackling of incarcerated individuals during pregnancy, labor, childbirth, or the postpartum period (though Mississippi and North Carolina just passed Dignity for Incarcerated Women laws recently, preventing people from being shackled while giving birth and requiring proper prenatal care for incarcerated parents, bringing that number down to 15). It’s unclear exactly how many pregnant people are incarcerated because data is spotty, but the Pregnancy in Prison Statistics Project by ARRWIP (Advocacy and Research on Reproductive Wellness of Incarcerated People) estimates that there are about 3,000 admissions of pregnant people to U.S. prisons and about 55,000 admissions of pregnant people to U.S. jails per year. Even where legislation bans the practice, shackling still takes place in these prisons and jails, sometimes because of legal loopholes that allow shackling when the incarcerated pregnant person is deemed a flight risk.

Often, shackling occurs in hospital and medical settings because care providers aren’t clear on legislation. “A lot of providers of labor and delivery units don’t even know what their laws are, or don’t know what the best practices and the guidelines from professional society are: not to shackle pregnant people,” says Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, founder and director of ARRWIP and author of Jailcare: Finding the Safety Net for Women Behind Bars. Dr. Sufrin cites a study of more than 900 labor and delivery nurses in which just over 7 percent of nurses polled were able to correctly confirm whether or not their state had laws against shackling pregnant people.

The lack of standardization of care for pregnant incarcerated people is also to blame for inhumane and dangerous practices, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. For example, a 2020 report found that at least 20 states had inadequate prenatal medical and nutritional care in prisons; Winn notes that her facility lacked clean water and any kind of prenatal vitamins, and she often had to hydrate herself with a sugary beverage during her pregnancy.

“The carceral system is designed for a specific purpose, and that purpose is directly misaligned with care,” says Jamila Perritt, MD, an OB/GYN and co-author of the American Journal of Public Health article Reproductive Justice Disrupted: Mass Incarceration as a Driver of Reproductive Oppression. (She adds that the “carceral mindset” exists in juvenile detention and immigrant detention facilities as well.) “It’s hard to believe that it is even a possibility to provide any humane medical care in a system that is designed to punish, to degrade, and to separate.”

The impacts of shackling on physical and mental health

On a basic level, shackling pregnant people can be detrimental to the physical health of the parent and child. There’s no way of knowing whether Winn would have carried her child to term if she had not fallen, but risk of falling is only one of the dangers that shackling poses to pregnant and birthing parents.

“The lack of humanity alone is enough to impact your physical state during the laboring process,” says Dr. Perritt. “The idea that you’d be subjugated and confined in any way during that process, to me, is deeply tied to not just your psychological well-being, but certainly your physical capacity.” Movement and walking around can be healthy and helpful with pain management during labor, she points out.

Shackling can pose risks during birth, too, in particular if there are labor complications such as abnormalities in fetal heart rate. It’s imperative for the birthing person to be able to move and be moved, especially in preparation for something like an emergency C-section, to ensure there are healthy oxygen levels for the baby in those urgent minutes prior to delivery.

Not to mention that this can be an incredibly traumatic experience for people giving birth, and may be especially so for Black women who live with the historical trauma of slavery in this country. The American Psychological Association also reports that shackling before or during birth can magnify already dire mental health conditions for incarcerated people, who are more likely to experience mental health issues than the rest of the population. “The price that women pay highly exceeds the crime and far exceeds the sentence. Most of us come back home way worse than when we left,” Winn adds. Because of that, the risk for PTSD and postpartum depression is higher among people who have been shackled during prenatal medical care in carceral custody.

This practice of shackling happens during the postpartum period, too. Parents may be either shackled during lactation (and unable to maneuver their bodies properly to feed their infants), or separated from their babies within the first 24 hours of life. That period is key for parent-child bonding as well as latching, if they choose to bodyfeed, according Dr. Perritt and Dr. Sufrin’s American Journal of Public Health article, which was co-authored by Crystal M. Hayes, PhD.

Beyond that, officers often shackle patients during other stages of carceral care, including routine pelvic exams and pap smears, Dr. Perritt says. Dr. Perritt notes that there’s often a great degree of public outrage for pregnant people being shackled because it is occurring during pregnancy, but less concern about people being shackled during other forms of medical care. “This is really about doing a deep interrogation of our desire to control and to punish the body of folks with a capacity for pregnancy, even during the most intimate moments—whether that is during labor and delivery, during your Pap smear, and in some cases, during your abortion care,” says Dr. Perritt.

What are potential solutions to end shackling of incarcerated people during reproductive care?

First and foremost, activists are working toward completely revolutionizing the carceral system and abolishing the prison-industrial complex. “Prison abolition—that’s the place to start,” Dr. Perritt says. While activists including Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, the co-founders of Critical Resistance, a movement to end the prison-industrial complex; anti-violence and prison abolition organizer Mariame Kaba; and transformative justice projects including Common Justice are leading this work, it’s simultaneously a priority to incorporate better standards of care while people are still incarcerated.

There needs to be a better oversight system for healthcare in prisons and jails. Right now, there isn’t any mandatory system of oversight or required set of health care services and standards. The National Commission of Correctional Healthcare is an organization that accredits detention facilities for proper healthcare standards; however, participation among prisons and jails is voluntary, Dr. Sufrin says. Activists in this space are also petitioning the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to call out the practice of shackling on a nationwide level, Dr. Perritt adds. Along with that, Dr. Perritt is the President and CEO of Physicians for Reproductive Health, which trains physicians to recognize their privilege as doctors and advocate for their patients in all reproductive-health-related situations, especially if the patients are in custody.

The care itself can also be improved with more care providers, such as doulas, advocating for incarcerated pregnant and birthing people and making sure they have agency over their own bodies. Research suggests that doulas working with incarcerated pregnant people could potentially have a positive impact on pregnancy outcomes—which are disproportionately poor for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous women, the same populations that are the highest represented in prisons and jails. Networks including the Minnesota Prison Doula Project and Alabama Prison Birth Project are supporting incarcerated parents through pregnancy and postpartum, and striving to keep them from being separated from their infants. “One of the challenges is that these programs are often unfunded—and this is valuable work, and should be funded as such, not volunteer work,” says Dr. Sufrin.

A positive change involves better legislation, including the federal First Step Act, which bans the shackling of pregnant incarcerated people in federal prisons. It passed in late 2018, in part thanks to the work of Pamela Winn. “I was fortunate to be able to write all the language pertaining to women in that bill,” she says. She recounts being present in Washington, D.C., when the House of Representatives passed the bill, after Representative Karen Bass read Winn’s story on the House floor as proof that the bill needed to pass. “It just took me from my cell in solitary feeling hopeless and helpless to being in the moment where it was like my dream had come true—to hear that someone cared enough about me to speak about me on the House floor,” she says.

The First Step Act covers people in federal custody, but it’s up to states to pass laws prohibiting the practice in state prisons and county jails. “Passing anti-shackling laws is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to dignified, respectful care for pregnant and birthing folks,” Dr. Sufrin says. “Even in the 35 states that have laws against shackling during birth, it still happens all the time.”

“Even in the 35 states that have laws against shackling during birth, it still happens all the time.” —Dr. Carolyn Sufrin

A long-term solution would be not incarcerating people who are pregnant, adds Dr. Sufrin. Legislation like Minnesota’s Healthy Start Act serves as a model for what this could look like. Signed into law in May 2021, it involves taking people who are pregnant and postpartum out of prisons and jails and placing them in supervised facilities like halfway houses, while providing them care and support for themselves and their babies for up to a year after giving birth. The law’s goals are to benefit the well-being of not just the parent and child, but also society as a whole: with more re-entry support for people returning to society, and hopefully less likelihood of those people reoffending as a result.

Fueled by each hint of progress against shackling during prenatal and postnatal care, reproductive justice activists press on. Today, eight years after her release from custody, Pamela Winn is the founder and executive director of the criminal justice policy advocacy organization RestoreHER. Recognized by Forbes and the ACLU as one of the leading activists in this field, she continues to fight for the passage of Dignity for Incarcerated Women bills on a state-wide basis. Winn believes formerly incarcerated people can steer the work of getting pregnant people out of prisons and caring for them better while in carceral facilities. “I would like for people to look at my accomplishments and understand that more resources must be provided to those with lived experience, because we know exactly what we need,” she says. “Just give us the support that we need, and let us lead.”

Oh hi! You look like someone who loves free workouts, discounts for cult-fave wellness brands, and exclusive Well+Good content. Sign up for Well+, our online community of wellness insiders, and unlock your rewards instantly.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.