Why the Dramatic Rise in Sexually Transmitted Infections Is a Major Wake-Up Call

As rates of sexually transmitted infections are rising, experts explain why knowing when to get STI testing is so important for your health.

When was the last time you got tested for sexually transmitted infections? Ask any group of people this question and responses will vary greatly based on their relationship status, age, insurance situation, and a multitude of other factors. But given that rates of most sexually transmitted infections are skyrocketing throughout the United States, it’s more important than ever to be certain of your status.

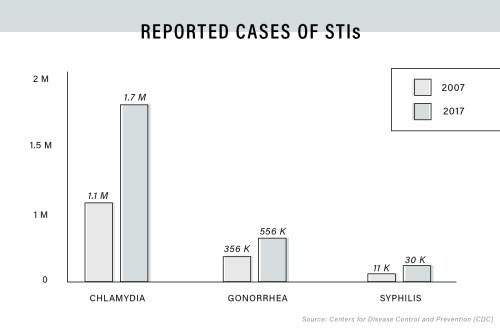

Let this sink in: According to the most recent CDC data, a record 2,295,739 cases of STIs were reported among both men and women of all ethnicities in 2017. Chlamydia diagnoses rose by nearly 7 percent from 2016 to 2017, with 1.7 million new cases recorded. Two-thirds of these cases were among men and women ages 15-24. There were 555,608 new gonorrhea cases in 2017—a massive spike of 18.6 percent from the previous year, which coincided with an alarming increase in cases of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea. Then, there’s syphilis. After dropping to all-time lows in the early 2000s, syphilis has made a remarkable comeback in recent years, rising by 10.5 percent between 2016 and 2017. Out of the new cases, over 30,000 were reported in adults—primarily gay and bisexual men—and 918 were found in newborns who contracted it from their mothers in utero. “Combined, reported cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis have reached the highest levels seen in more than two decades,” says Elizabeth Torrone, PhD, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention.

Oh, and let’s not forget about HPV and herpes, which aren’t as closely tracked by the government but are still incredibly common. Around 80 percent of sexually active people will contract HPV in their lifetimes, while more than one in six people aged 14-49 have genital herpes. HIV is one of the few diseases that has remained more or less stable in recent years, thanks to new preventative drugs and treatment options, but we’re still far from vanquishing it.

Some experts believe that rising STI rates might be attributed to a growing number of people who get screened and, subsequently, diagnosed. But it’s hard to say to what extent that’s true. No definitive data on nationwide screening rates is currently available. And while some statistics indicate that testing for certain diseases has increased since the early 2000s, particularly among young women, disease experts don’t think that’s the primary driver behind our nation’s current STI epidemic. In fact, the general consensus is that many people who are at risk still aren’t getting tested, which can only be contributing to the problem. Consider the fact that congenital syphilis—when a mother passes the infection on to her baby—is currently on the upswing, indicating that women aren’t receiving the routine screenings and treatment they need during pregnancy.

“It’s concerning that this is the fourth year in a row that we’ve seen an increase in STIs,” says Peter Leone, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of North Carolina. “It’s not like there’s been this massive surge in screenings that can contribute to the numbers going up. So the question is, why are we seeing this increase?” Given that untreated STIs like chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis can lead to some pretty dire consequences—including infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, and an increased risk of contracting HIV—it’s pretty crucial that this question gets answered.

There are a lot of factors behind the recent rise in STI rates

Experts have many theories about why we’ve seen a spike in STI diagnoses over the past four years. For one thing, the rise of dating app culture could be playing a role, says Victoria Mobley, MD, the HIV/STD medical director at the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. “There’s now this ease with which we’re now able to interact and find [sexual] partners,” she says. While dating app users don’t necessarily have more sexual partners than non-users, Dr. Mobley points out that these apps exponentially widen our social circles, putting us in contact with people we may not have encountered before. When your network expands, your chances of being exposed to an STI—or transmitting an STI into a new network of people—may expand as well.

Dr. Leone believes that a rise in risk-taking behavior could also be happening. First off, he says, the 2017 rise in syphilis and gonorrhea appears to be linked with the rise in opioid addiction and substance abuse. “I think the issues there are risk behaviors associated with drug use and lack of access to care for a lot of these folks,” he says. Studies show that substance use among young people is linked with an increase in sexual risk-taking—for instance, engaging in sex without a condom or having multiple partners—which increase one’s risk for contracting an STI.

Another aspect of the trend, ironically, could be that we’ve made great strides in treating HIV over the past decade. This is an inarguably good thing, but it may also make people historically most at risk—namely, gay and bisexual men—feel a false sense of security about STIs, and potentially expose themselves to other diseases as a result. “[Effective treatment] has really led to an increase in sexual risk-taking behavior among men who have sex with men and a decrease in the use of condoms,” Dr. Leone says, noting that the increase in STIs among this demographic started around the same time that effective antiretroviral treatment became available, back in the late ’90s. Indeed, men who have sex with men are disproportionately affected by certain STIs today—for instance, 68 percent of syphilis cases in 2017 occurred within this group.

And then, of course, there’s the testing issue. We have a pretty good idea of who should be getting tested and how frequently: The CDC currently provides detailed STI screening recommendations, which were last updated in 2015. (Dr. Torrone notes that these STI screening guidelines are set to be revisited this year.) And while transmission patterns have indeed shifted lately—a growing number of women are being diagnosed with STIs, for instance—the experts I spoke with agreed that the problem doesn’t so much lie with the recommendations themselves, but the fact that these recommendations aren’t always being followed.

So why aren’t people being tested for STIs as they should?

Again, this is a complicated question with lots of different facets to explore. On one hand, there are several barriers that prevent people from getting into the doctor’s office in the first place. Dr. Torrone says that drug use and discrimination can prevent people from seeking out or receiving quality STI care. She adds that socioeconomic factors can also play a role. Those with or without insurance can often get free testing at community clinics, yet federal and state funding for STI prevention has dropped about 40 percent over the past 15 years, which means there are fewer resources being devoted to public health programs targeting these diseases. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently finalized a rule barring abortion providers, including Planned Parenthood, from receiving federal Title X funds—despite the fact that these clinics also offer STI testing and other women’s health services under their roofs. This may eventually make STI testing access even harder to come by for many people.

Lack of awareness may also be preventing people from getting their recommended screenings. Many STIs, like chlamydia and gonorrhea, can live in the body unnoticed, so people might not think they have a reason to be tested. “People don’t really know much about STIs—the thought is that you have to have symptoms, and that’s just not the case,” Dr. Leone says. Indeed, diseases like chlamydia and gonorrhea often present with no symptoms, or symptoms so mild that women might think they’re dealing with a yeast infection or bacterial vaginosis. “You can still get a disease without having symptoms at the time of acquisition. A lot of this is that we need to have a much broader campaign around sexual health.”

“People don’t really know much about STIs—the thought is that you have to have symptoms, and that’s just not the case. We need to have a much broader campaign around sexual health.” —Peter Leone, MD

Dr. Mobley adds that people can also downplay their risk for STIs, thinking that since they use condoms that they have nothing to worry about. But the truth is that condoms aren’t 100 percent effective. “[A man] may have put a condom on, but he may not have put it on appropriately or in time,” she says, noting that some STIs, like syphilis, can be transmitted by skin-to-skin contact during foreplay.

There’s also an enduring stigma around STIs that can lead people to avoid getting screened, says Dr. Mobley. “Nobody wants to be told they have an STI, let alone have somebody find out that they were diagnosed with an STI,” she says. Although it’s not the same kind of stigma carried by HIV—which is still (incorrectly) considered a death sentence by many—there’s still a lot of shame and embarrassment that can creep up around the STI screening process itself. Some people may be nervous to talk about their sexual habits with their primary care provider, or fear that a family member or acquaintance may find out they went to a neighborhood sexual health clinic. “[The chance of] your neighbor or your mom’s church friend seeing you going in there, that may drive people to not want to get tested,” Dr. Mobley says. The same goes for teens and 20-somethings on their parents’ insurance, who may be afraid that mom or dad will get the bill for their test. And then if an STI diagnosis does occur, a person has to have an uncomfortable conversation with their partner—a prospect that might lead them to put off getting tested.

Since the health consequences are greater for women, the burden falls on them to get routine screenings.

Even if someone does visit the doctor routinely, that doesn’t mean the doctor will offer to screen them appropriately, or even at all. “We’re still having a really difficult time getting [clinicians] to know what tests to order and what sites to screen,” says Dr. Leone. “We frequently talk about STIs being tied to risk behavior, but it’s hard for [clinicians] to assess risk.” Take gonorrhea, for example. Dr. Leone says that, ideally, doctors should be swabbing patients’ throats, genitals, and rectums when screening for this disease, as it can be transmitted through oral, anal, and vaginal sex. (Untreated gonorrhea of the throat, specifically, has been linked to the mutations that are causing bacteria to resist antibiotics.) But most of the time, only the genitals are tested, which could be leading some infections to go undiagnosed. “[Doctors may be] uncomfortable with swabbing someone’s throat or rectum, and they make assumptions,” he says. “If it’s a woman, they may think ‘Well, she wouldn’t have engaged in anal sex.’ Or there may be men who don’t identify as being gay, but they may be having sex with men.”

Yes, it seems odd that doctors, of all people, would feel awkward talking about sex with their patients, but Dr. Mobley agrees that it’s not uncommon. “Some providers may just think their patients ‘aren’t those kinds of patients,'” she says. “[Questions like] ‘Do you have sex with men, women, or both?’ and ‘Do you have sex with individuals outside of your marriage?’ may bring some discomfort, even for [health care providers],” she says. And, as-such, people may not be getting the screenings they need.

Knowing when to get STI testing is critically important, according to experts

As they stand right now, routine STI screening recommendations are a bit different for everyone, based on age, gender, sexual orientation, and lifestyle—all of which impact your risk factors for specific diseases. At minimum, per the CDC, all sexually active women under 25 should be screened for gonorrhea and chlamydia each year, as should women over 25 with multiple sexual partners or a partner with an STI. Pregnant women should receive a full STI screening panel early in pregnancy. All men who have sex with men should get a yearly test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis, or every 3-6 months if they have multiple partners. And, of course, any person exhibiting symptoms of an STI should obviously see their doctor. Basically, if you think you could have an STI, there’s only one way to know for sure.

As for heterosexual men? They’re curiously absent from the CDC website’s screening guidelines. A CDC spokesperson tells me that there’s no available evidence that universally screening asymptomatic heterosexual men will have a significant impact enough impact on public health to justify the cost. If you heard the same record-screech noise as I did when you read that statement, here’s the deal: There’s only so much funding to go around when it comes to STI screenings, and, as mentioned before, that funding is on the decline. “A lot of the funding [allocation] for STI screening has to do with making sure women can get pregnant and not transmit infections to their babies,” Dr. Leone points out. If a woman has an untreated STI, she risks infertility, miscarriage, and other reproductive health problems, whereas such side effects are less common in men. So, since the health consequences are greater for women, the burden falls on them to get routine screenings [eye roll].

“I’d say anyone who’s sexually active should be tested for STIs at least annually, and more frequently if you’re identified as someone with an increased risk of acquiring an STI.” —Victoria Mobely, MD

The other aspect to this, says Dr. Leone, is access to care. “Because of pap smears and hormonal contraception, women have more routinized primary care more than men,” he explains. “Most men in their teens and 20s don’t have a primary care provider or go in for any regular visits, which is what you want to do to reduce the overall prevalence of these infections.” So it follows that it would be easier for doctors to add a routine STI check to a woman’s existing reproductive health exam, rather than to convince men to visit the doctor when they aren’t experiencing symptoms. If a woman is diagnosed, several states have programs in place that allow her partner to get treatment without visiting a doctor himself. (I mean, why should men have to take the same responsibility for their wellbeing as women? [double eye roll].) That said, it’s important to keep in mind that the agency’s guidelines aren’t hard-and-fast rules—it’s up to doctors to decide whether an individual person’s risk factors warrant screening or not, no matter what their gender.

To take the “should-I-or-shouldn’t-I” guesswork out of it, Dr. Mobley recommends a more straightforward approach. “I’d say anyone who’s sexually active should be tested for STIs at least annually, and more frequently if you’re identified as someone with an increased risk of acquiring an STI—if you’re someone who has multiple partners or if you have any concern that your partner may not be monogamous,” she says. (Yes, her yearly STI screening advice should probably go for people in monogamous relationships, too. Partners aren’t always faithful, after all.) Dr. Leone adds that you should ask to be screened everywhere you’ve had sexual contact, which may include your mouth, your anus, and your genitals.

Doctors and patients should really be thinking of STI screening as part of preventative care, says Dr. Mobley, similar to getting an annual blood-pressure and cholesterol check. “I think it would really turn the tide if STI screenings were ordered by primary care physicians as part of your routine healthcare practice,” she says. “If they were asking questions about your sexual risk and history as part of the routine medical exam, that kind of thing would help remove the stigma and I think people would be more willing to be tested.”

And in this era of at-home health testing, you don’t even need to go into a doctor’s office to be tested for STIs. Brands like EverlyWell and LetsGetChecked offer DIY testing kits that screen for every potential infection, with prices starting under $100. (EverlyWell’s chlamydia and gonorrhea test, for example, is $49.) Think of it as part of your self-care routine. Peeing into a cup may not be as fun as a face mask—but the peace of mind that comes from it is sure to be wildly beneficial for both your physical and mental health in the long run.

Sign Up for Our Daily Newsletter

Get all the latest in wellness, trends, food, fitness, beauty, and more delivered right to your inbox.

Got it, you've been added to our email list.