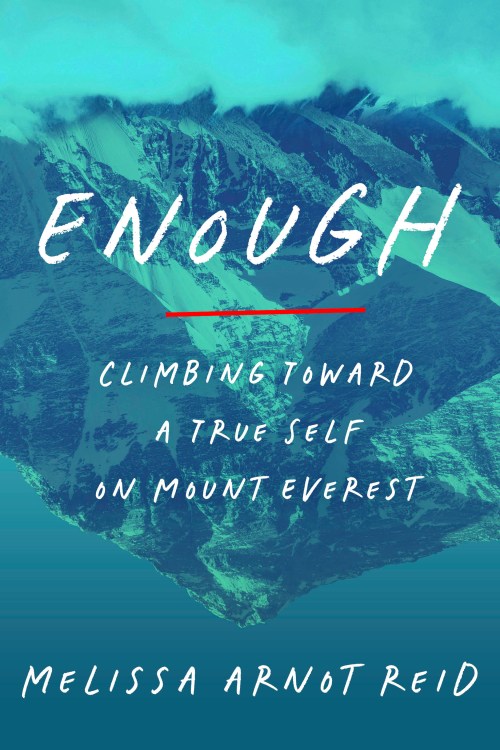

She Made History on Mount Everest—Her New Memoir Tells the Real Story

Melissa Arnot Reid peels back the layers of her career fame in a powerful debut.

Ever feel like you’re on stage—performing your “best self” but terrified someone will spot the cracks? You could blame social media, or the societal pressures that have been put on women for generations. (And you wouldn’t be wrong.) But we could also, partly, blame ourselves.

In her blisteringly honest memoir, ENOUGH: Climbing Toward a True Self on Mount Everest, mountaineer Melissa Arnot Reid peels back the layers of her career fame to tell the story of the woman who just wants to be known (and, more importantly, loved)—flaws and all.

If you’re not already familiar with Reid, let me quickly catch you up to speed. As one of the world's greatest climbers, her resume includes six successful summits of Mount Everest in nine attempts (the most of any American woman). In May 2016, she became the first American woman to successfully summit (and safely descend) Everest without supplemental oxygen.

I first interviewed Reid in 2014 for a story I was working on about chasing “impossible” goals. Her perspective was awe-inspiring: “A lot of people ask if there’s some trait I have that makes me better at climbing at high altitudes than other people,” she told me. “Absolutely not. I’m not naturally fit; I have to work really hard and train really hard to be ready. But I do have this extraordinarily high tolerance for being uncomfortable. I have a sort of way of seeing it joyfully. I think that is what sets me apart from other people.”

In Enough, she takes that willingness to embrace discomfort to a whole new level. What grabs you immediately is Reid’s clear intention to be the messy narrator of her own legend. She lays out every private misstep—from seeking love and safety as a young girl to the guilt of trading authenticity for applause—and dares us to see our own hidden corners in the glare of her self‑examination. She manages to put into words the private struggles so many of us have felt: female competitiveness, insecurity, and the deep-seeded pressure of perfection; the longing to be accepted for exactly who we are, and the fear of showing people exactly who we are.

Repeatedly throughout the book I found myself stopping to think, I can’t believe she admitted that. The internal thoughts she never said out loud; the actions that didn’t have witnesses. It would have been easier to leave it out. No one would have known.

But it goes back to what she told me more than a decade ago: “That discomfort makes me feel happy, which I get is strange. But it makes me feel like I can appreciate other uncomfortable situations because I’m intentionally enduring that; I’m learning how to be okay when I’m physically or even emotionally uncomfortable. It’s this mentality of ‘I just have to bite the bullet and get through this. It’ll be okay on the other side.’ Whether it’s going to school, work, climbing Everest, that sort of mindset has played into everything I’ve done.”

Page after page, chapter after chapter, you come to realize something important: You don’t have to share the same background—or altitude—to find your truths mirrored in someone else’s journey. Enough feels like swapping stories with a big sister who’s mastered the art of tough love. Reid’s brutal self‑examination dares us to shine that same spotlight on our own hidden corners. To pause and ask, how honest is the story I’m telling myself?

What makes this book so empowering is that Reid doesn’t stop at confession. She challenges you to follow her down a tougher path: accountability. It’s far easier to blame the system, the circumstances, or the people around us. But in owning our less-than-perfect parts of the play, we can begin to feel how “enough” we are, despite them.

Keep scrolling for an exclusive excerpt—your first step into the raw, beautiful truth that only Reid can guide you through.

Read an excerpt from Melissa Arnot Reid’s 'Enough'

2014: Mustang, Nepal

The blank slope of firm white snow the consistency of Styrofoam sprawled above me into the unknown. I looked down at Ben, his ice tools touching the ice and snow in front of him. The slope was steep enough that all he had to do was lean gently forward, as though smelling a pot of simmering soup, and his upper body would be inches from the surface. His red helmet contrasted with his yellow jacket and for a moment I thought he looked like a hot dog. Our teammate and photographer, Jon, was on the slope to my right, looking for an easier way to ascend.

I took a deep breath, absorbing the tiny oxygen molecules at 20,000 feet above sea level and begging them to wash me clean. Just a short distance above me was the summit of this unclimbed peak, sprinkled with loose rocks and frozen white ice, as pure as a virgin bride. I had long forgotten what purity even looked like, and when I saw it now in this mountain, it made me feel dirty.

We had spent the previous weeks exploring the unmapped zone of northwestern Nepal, looking for a trio of peaks that had only recently been opened by the government for climbing. I wanted to find mountains that were challenging but that would possibly allow someone with mediocre climbing skills to ascend them, not just so I could bring clients, but also to have an adventure that wasn’t life-threatening. Basically, I was looking for a steep walk in a remote place. And now, after three days spent up high, we had found it. I was going to complete a first ascent of an unclimbed peak.

I felt giddy with the excitement of knowing that it was unlikely humans had stood here before. I imagined what it was like for the British mountaineers from the 1920s, and I almost wished I had brought a flag to plant. Of course, I wasn’t here out of some sense of patriotism or exploration, but rather a sense of escape. And the kind of escape I was looking for required going deep into unmapped terrain, free from humans other than my small team. It required nearly getting lost on the Tibetan tundra to see if I could catch a glimpse of myself.

The death and the tragedy from the previous seasons were weighing heavily on me, reminding me how finite this life is. It was forcing me to look at my own choices and ask myself if I wanted to live my life pretending to be someone I wasn’t or if I wanted to be truly known. I was hoping some time in the quiet of these mountains would help me find some answers.

The irony was that my career was rising for my suffering. I’d spent the last seven years on Everest in the spring, arriving at the summit five times. I spent every fall returning to the Himalayas, deepening my connection with the people, and sharing trekking peaks with clients. When winters arrived, I began a rigorous training regimen and took multiple trips to New York City to meet with the media and tell them how I was exceptional and interesting and worth keeping their eye on. I wrote a semi-honest essay in Women’s Health about how marriage was my real Everest. I sat for filmed interviews with morning talk show hosts to discuss what it was like in the death zone, and more important, what it was like for a woman. The wave of success and attention was a steady and reliable swell, and I was surfing its every curve.

But at the same time, I was shrinking into a shell of a human. The only person I was anymore was the person the media saw, single-dimensioned and uncomplicated. Everything else was turning numb and dull, cloaked in dishonesty. I had kept cultivating my distance from my husband, and drinking in the attention of all the boys and men on expeditions. I was refusing every attempt at being a good partner, a good wife, or even a good person. The more I hid from myself and all that I was carrying, the more I sort of just disappeared into a mirage of the person the world saw.

Excerpted from ENOUGH: Climbing Toward a True Self on Mount Everest by Melissa Arnot Reid. Copyright © 2025 by Melissa Arnot Reid LLC. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.